Should the terminally ill control how they die?

The following is a script from "Aid in Dying" which aired on March 13, 2016. Dr. Jon LaPook is the correspondent. Denise Cetta and Kevin Finnegan, producers.

Brittany Maynard was dying of brain cancer when she decided to drink a lethal prescription to end her life. She was just 29 years old. Her decision made her a symbol in the debate about how much we should be able to control the time and manner of our own death.

This is not euthanasia, when a doctor gives a patient a lethal injection. That's illegal in all 50 states. Aid-in-dying, or what opponents call "assisted suicide" and supporters call "death with dignity," relies on people taking the medication themselves. Oregon became the first state to legalize it 18 years ago, but because a nurse or doctor is rarely present, it's remained mostly a private affair, practiced behind closed doors. We wanted to hear from patients and family members who've experienced it and are fighting to make it legal nationwide.

Brittany Maynard had been married less than a year when the headaches began. This MRI revealed a deadly mass -- it turned out to be brain cancer so aggressive doctors gave her only six months to live.

[Brittany Maynard, CBS News interview: All evidence points to the fact that this cancer will kill me.]

Three weeks before she died, Brittany, bloated by medication used to control brain swelling, explained in an interview with CBS News why she was grateful to find a legal way to end her life.

Brittany Maynard: Being able to take a medication that allows me to slip into a sleep in five minutes and pass away most likely within the half hour sounds a lot better to me just as a human being, as a daughter, as a wife. And I think it sounded better to my family than reading about the alternative.

The alternative, husband Dan Diaz says, was for Brittany to endure weeks of agonizing decline.

Dan Diaz: Brittany said, "I'm not afraid to die. At this point I am not afraid of death. But I am afraid of being tortured to death."

Dr. Jon LaPook: What did she mean by being tortured, specifically? What was she afraid of?

Dan Diaz: So those symptoms that she knew was coming for her, the torture for her would've been losing her eyesight and not knowing now who's in the room. I mean, the seizures were bad enough as it was.

Dr. Jon LaPook: How about pain?

Dan Diaz: Pain was just constant.

But aid-in-dying medication wasn't legal in their home state of California. So in the spring of 2014, Brittany told Dan it was time to pack up and head to Oregon...the closest of four states where it was legal. Once she became an Oregon resident, Brittany had to make two verbal requests -- 15 days apart -- to a doctor, fill out this written form, and have two physicians confirm she was mentally competent and expected to have less than six months to live.

The medication often prescribed is secobarbital. A barbiturate that in small doses causes sleep, in large doses, death. Here in Oregon a patient comes in with a prescription and gets a bottle of 100 of these capsules. Each one has to be opened up individually and one by one the powder poured into a glass and the contents dissolved in water.

[Brittany holding the medication bottles

Brittany Maynard: This is the prescription for Death with Dignity.]

Since 1997, more than 1,500 prescriptions have been written in Oregon -- over a third who requested it, never took the medication.

Dan Diaz: I think people think, "Oh well, you apply for that medication. And then, you get that. And then, you're kinda done." No, no, no. You apply for that medication. You secure it. You put it in the cupboard. And you keep fighting. And we sent her packet of medical information to Duke and Mayo Clinic and UCLA and everywhere that we possibly could to see what's out there. So you have cancer, you fight.

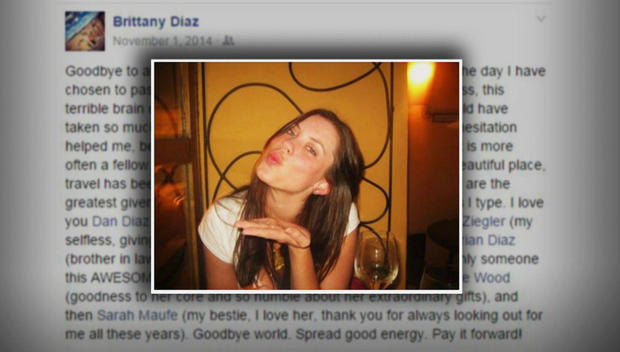

Brittany's tumor kept growing - invading her brain, and causing seizures so violent they left her unable to speak for hours. She feared a stroke might soon leave her paralyzed and unable to take the lethal medication. So on November 1, 2014, she posted this photo on Facebook, said goodbye, and drank the five ounces that would end her life.

Dr. Jon LaPook: Do you mind sharing the last few moments you spent with her?

Dan Diaz: Um, we were um, in the room, in our bedroom. And I was right next to her. There's no, like, dark cloud looming. It-- it-- the feeling is simply of love and support. Within five minutes, Brittany fell asleep just like I've seen her do a thousand times before, very peacefully. Within 30 minutes, her breathing slowed to the point where she passed away.

Dan Diaz has kept in touch with Dr. Eric Walsh, the Oregon physician who prescribed the medication. Dr. Walsh couldn't talk about the specifics of Brittany's case due to patient privacy, but for the first time has agreed to discuss why he prescribed the medication to her, as well as to 19 others.

Dr. Eric Walsh: When somebody's facing the end of their life shouldn't they be in control? Shouldn't I be able to help them when they're suffering, and the burden of living becomes intolerable to them?

Dr. Jon LaPook: We hear a lot about statistics about the Oregon experience. But it's a lot of sort of statistical detail, and not a lot of emotion.

Dr. Eric Walsh: You're right, the statistics are very dry. Someone said that statistics are human stories with the tears washed off.

Dr. Jon LaPook: Tell me about your tears, perhaps once you're involved in this.

Dr. Eric Walsh: You know, we categorize tears into a single adjective. Tears of joy, tears of sorrow, tears of regret. But actually in the physician aid-in-dying these are tears that contain all of those adjectives.

Elizabeth Wallner looks healthy, but has advanced colon cancer that multiple surgeries, radiation and months of chemotherapy are barely keeping at bay. She sued the state of California for the right to end her life with medication.

Dr. Jon LaPook: Why do you feel so strongly about legislation?

Elizabeth Wallner: Mostly, for my son. I remember-- you know, he was 15 when I was diagnosed. And I just remember this one time I was in the bathroom and he was taking care of me while I was getting sick and I looked over at him and his face was just absolutely devastated. And I just realized in that moment that I can only take so much and my family can only take so much.

Elizabeth Wallner: This child is my knight in shining armor.

Nathaniel Wallner, now 20, says he savors the time he has left with his mom, but is realistic about what lies ahead.

Nathaniel Wallner: Four and a half years of fighting cancer you've gone through enough pain and suffering.

Elizabeth Wallner: Yeah.

Dr. Jon LaPook: I guess there's saying that, and there's feeling it for sure. And I can see it in your eyes. And then there's when the moment comes. Is there a little bit of a question mark in your head about how you'll feel then?

Nathaniel Wallner: I don't think so.

Dr. Jon LaPook: You've thought about this a lot.

Nathaniel Wallner:: Yeah. There isn't a day where I won't wish that there would be more time. But there will very easily be a day where I wish there was less suffering.

Elizabeth, who was raised Catholic, disagrees with those who say aid-in-dying goes against God's will.

Elizabeth Wallner: I don't believe in a God that would want me to suffer and struggle to death. I don't believe in an in-compassionate God. The only argument that I've heard that actually makes any sense is that there is some beauty in struggle. And I agree with that, there is beauty in struggle. But four and a half years, end of a struggle, I'm good, you know?

"There isn't a day where I won't wish that there would be more time. But there will very easily be a day where I wish there was less suffering."

Oregon physician Dr. William Toffler, who's taken care of terminally ill patients for 40 years, worries doctors prescribing medication may not know people well enough and might miss signs of depression. He believes one reason Oregon's legislation is flawed is that the state isn't required to track what happens to people after they fill their prescription.

Dr. William Toffler: Ninety percent of the time here in Oregon there's no doctor present. So there's really a shroud of secrecy under this whole thing. The only cases that come to light really aren't very reassuring.

Dr. Toffler is referring to the fact that out of the nearly 1,000 people who've taken the medication, about 30 cases of complications have been reported to the Oregon Health Authority. Mostly vomiting ...and six patients regained consciousness at least once before dying.

"Ninety percent of the time here in Oregon there's no doctor present. So there's really a shroud of secrecy under this whole thing. The only cases that come to light really aren't very reassuring."

Dr. William Toffler: It's basically corrupting the practice of medicine where we are no longer providers for the health and wellbeing of patients until they, they die naturally. But we're now actually hastening death by giving people massive overdoses. This is an inherent conflict of interest for doctors.

Dr. Toffler says he faced these issues with his own wife, Marlene, when she was dying of cancer two years ago.

Dr. William Toffler: Even with breathing difficulties, like my wife had with her terminal illness. And she had that fear. I had to help her to understand, "Marlene, we can get through this together. We've got medicines to help relieve the air hunger. It's not gonna be that bad." And it wasn't.

[Walsh making home hospice visit

Bob Williams: Hi Dr. Walsh, how are you?]

We joined Dr. Walsh as he visited one of his hospice patients, Robert Williams, at home. Dr. Walsh says the majority of his patients who are terminally ill receive hospice care, compassionate, professional end-of-life treatment that can include anti-anxiety drugs and powerful narcotics like morphine. Though usually extremely effective at keeping people comfortable, in rare instances, standard hospice care doesn't work well enough. In those cases, Dr. Walsh says, one option is something called palliative sedation.

Dr. Eric Walsh: When the physician decides that suffering is intolerable, the physician prescribes a medication which puts the patient in a coma.

Dr. Jon LaPook: Which is what?

Dr. Eric Walsh: Well, usually it's a barbiturate. The nurse administers it. It's given until the person is asleep. The person sleeps for three days, five days. I've had someone live 10 days, still excreting, still breathing, with the family at the bedside wondering, "When is this going to end?"

That was the kind of death Californian Jennifer Glass was adamant she did not want. Last year, battling lung cancer, she shared her fears in online videos.

[Jennifer Glass video

Jennifer Glass: The idea that it will end by me drowning in my own lung fluid while my family watches me suffer; that is terrifying.]

But last August, when standard hospice care was no longer enough, Jennifer Glass was put in palliative sedation, which lasted five and a half days. Though for most people it leads to a peaceful death, Jennifer's husband, Harlan Seymour, says it did not work for her.

Harlan Seymour: There were times when she was gurgling, where she was foaming through the mo-- the mouth and nose. And I feel that she was suffering on the inside. That it was really a terror on the inside.

Dr. Jon LaPook: And what was it like for you to watch this?

Harlan Seymour: To be there and see my beautiful wife suffer and wither away and have difficulty breathing. It was heartbreaking.

Dan Diaz says he's grateful his last memories of his wife, Brittany Maynard, are of walking these woods in Oregon.

Dan Diaz: The last time I was here, Brittany was at my side. The last time I did anything here, it was her and me and with the dogs.

Before Brittany died, Dan promised her he'd work to make aid-in-dying legal in their home state of California. So he quit his job and teamed up with the organization compassion & choices. Last September, a bill was passed permitting aid-in-dying. It will go into effect this June.

Elizabeth Wallner says she will now be able to control not only her suffering -- but where, with whom and when she dies. Something she's grateful for since speaking with Dan Diaz and Harlan Seymour about their wives' final days.

Elizabeth Wallner: Those deaths were really, really different. And Jennifer died in pain, and in fear, and panicking, and thinking she was drowning.

Dr. Jon LaPook: Whereas Brittany?

Elizabeth Wallner: Brittany crawled into bed with her husband. He had her arms around her, and she was asleep in five minutes. And both women are gone. And yet the difference of what they left behind is so profound.

Dr. Jon LaPook: And it sounds like from what you're saying your decision to

perhaps take the medication will be a final act--

Elizabeth Wallner: Absolutely.

Dr. Jon LaPook: --of protecting your son.

Elizabeth Wallner: Absolutely. I just want him to remember me laughing and, you know, giving him a hard time, and telling him to brush his teeth, and knowing that I would-- I would, you know, walk across the sun for him.