Remembering Charles Curtis, the first Native American vice president

Just two blocks away from the Kansas State Capitol in Topeka, you'll find a stately brick home with two domes.

"My mom loved the house; it's probably one of the prettiest houses in Topeka," said Patty Dannenberg. Her parents, Nova and Don Cottrell, purchased the local landmark in 1993.

"It hadn't been well cared for. It needed a lot of work," Dannenberg said.

Although the couple was retired, they spent the next 25 years painstakingly restoring the home's parquet flooring, gleaming chandeliers and stained glass, eventually opening it to the public as a museum, dedicated to the man who once lived there: Charles Curtis.

Dannenberg said, "I don't think many people around really knew much about him or realized how remarkable he was."

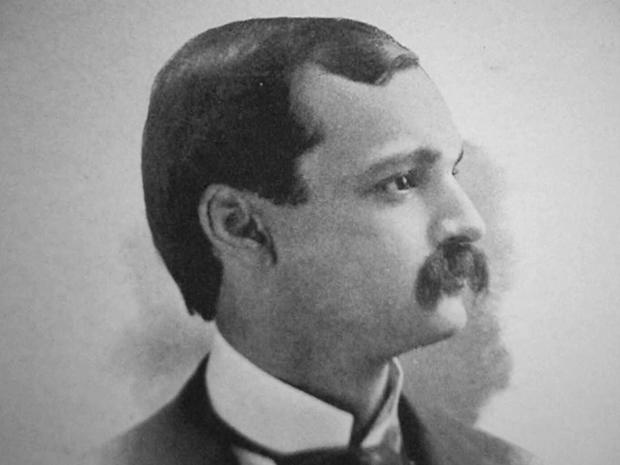

Remarkable indeed. Ninety-two years ago Charles Curtis was inaugurated as America's first (and only) Native American vice president. Curtis was a member of the Kaw (also called Kanza) Nation.

"The Kaw people are the indigenous people of Kansas," said James Pepper Henry, CEO of the First Americans Museum, slated to open in September in Oklahoma City, and vice chairman of the Kaw Nation. "I would say 99% of everyone in this country does not realize the state of Kansas takes its name from our people, the Kaw people."

Curtis was born in 1860 in what was then the Kansas Territory to a White father and an Indian mother. His mother died when he was just three, and he was left in the care of his Indian grandmother.

"He lived with the Kaw people on the reservation," said Pauline Sharp, a member of the Kaw Nation. "He learned how to ride horses, he could speak the language."

By 1873 the Kaw Nation, once millions of acres in area, had dwindled to little more than a burial plot, and the few hundred surviving members were being forcibly relocated south to what would become Oklahoma.

Sharp said, "They walked to their new home in Indian territory. Took them 17 days. People got sick. There was typhoid, even starvation."

Thirteen-year-old Charles expected to join the migration, but his Indian grandmother commanded the boy to stay in Topeka with his White grandmother and assimilate.

Henry said, "She wanted the best for him, and the best for him was to go live with his White family. And it turns out his grandmother was right."

Correspondent Mo Rocca asked, "Had he gone with her, would we be talking about him today?"

"We wouldn't know who Charles Curtis was had he gone with his Native grandmother to Oklahoma. In fact, he may not have even survived."

Instead, Curtis thrived. He became a successful lawyer, and was elected to the U.S. House of representatives.

Rocca asked, "Do you think having to go between worlds sort of trained him for politics in a sense?"

"I think that's true," Henry replied. "I think that being a mixed blooded person, in some ways being an ambassador between two worlds, did prepare him for American politics."

In the Senate, Curtis, a Republican, became a force, serving as Majority Leader. An advocate for women's rights, Curtis proposed the very first version of the Equal Rights Amendment.

Henry said, "Women have always had leadership roles within our tribe, and been really the backbone and strength of our tribe."

"I'm guessing that might have been a factor in clearly his belief on this issue?" asked Rocca.

"Well, knowing my Native grandmother, I know his Native grandmother had a strong influence on him. Certainly mine did."

But for Native Americans, the legacy of the man known as "Indian Charley" is decidedly mixed.

Many of the assimilationist policies he backed had ultimately devastating effects on the lives of Indians, leading to the dissolution of tribal governments and the break-up of communal lands.

"I think he believed he was doing the right thing," said Henry. "Had he been alive today, I think he would have understood that some of the things that he believed in at that time did have a significant negative impact on Native peoples."

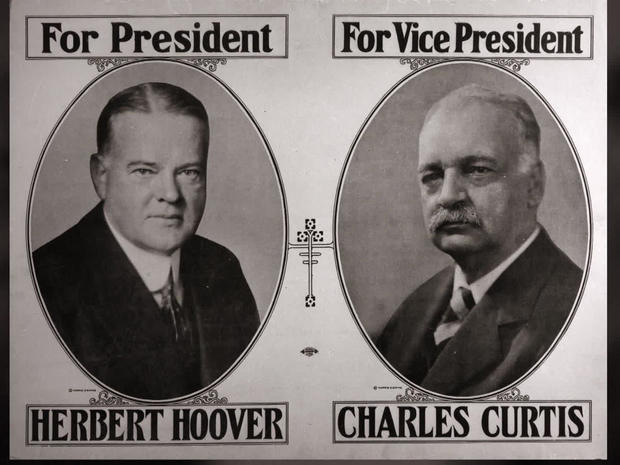

In 1928 Curtis, running with Herbert Hoover, was elected the 31st Vice President of the United States. He was given little to do in the office, though he did preside over the opening of the 1932 Olympic Games in Los Angeles. But with the onset of the Great Depression, the ticket's bid for reelection went down in flames.

After Curtis' death in 1936, his name quickly faded.

As for his former home in Topeka, Don and Nova Cottrell died last year, months apart. The house is now for sale. Patty Dannenberg hopes that whoever buys the Curtis home will preserve it.

Rocca asked, "What would be lost if the house weren't there?"

"I think a lot of history would be lost," she replied.

And as for the Kaw Nation, they've rebounded in number, and in 2002 purchased acreage for a memorial park in Kansas – a return to their ancestral land.

Pauline Sharp said, "We danced on our land in Kansas for the first time in 142 years."

How did that feel? "It felt wonderful to be back home!"

Rocca asked, "How would you like Charles Curtis to be remembered?"

"That's a hard one," said Sharp. "As the first Native American to make it that high in the United States government, that's a source of pride for us. And I want people to remember him, I think, in a good way."

For more info:

- Charles Curtis House (Town & Country Real Estate and Auction)

- First Americans Museum, Oklahoma City, Okla.

- The Kaw Nation

- Thanks to Dave Kendall and "Sunflower Journeys" (KTWU Topeka)

Story produced by Mary Lou Teel. Editor: Steven Tyler.

See also:

- More presidential history from Mo Rocca (Playlist)